Sharing personal information with a company or organisation is often a vital and necessary part of doing business, or indeed functioning in modern society. But your credit card details, address, telephone number or communication details, all of which are considered personal, can be damaging in the wrong hands.

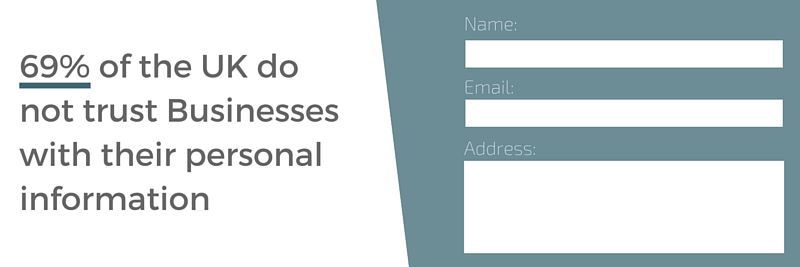

Despite the need for sharing this information, as many as 69% of the UK do not trust businesses to protect their personal details. Our most recent study highlighted a general wariness about companies holding onto sensitive information.

Amongst the over 65s, an overwhelming 82% said they do not trust firms with their personal details, whereas in the 18-24 bracket, almost half (47%) claimed they weren’t worried about companies keeping hold of their information.

However, it also emerged that a large proportion of people do not take measures themselves to protect their own personal documents, with up to 37% of people in the UK admitting to not shredding their personal documents properly when they’re finished with them.

Our figures also confirmed that youngsters are most guilty of failing to keep their sensitive information out of the wrong hands. This is worrying given recent studies by fraud prevention experts Cifas, which showed that young people are consistently being targeted by criminals, with a 52% rise in identity theft victims under the age of 30 between 2010 and 2015.

In light of the recent Brexit decision, there is a great deal of uncertainty surrounding data protection legislation, as it’s unclear how the UK will fare if it is not obliged to adopt Europe’s General Data Protection Regulations. These are supposed to take effect across EU states in May 2018, by which point the UK may have left the union.

What should businesses uphold?

When holding your personal data, businesses are bound by the Data Protection Act, 1998. Whilst the act itself may be close to 10 pages long, it presents 8 key points that businesses should follow when holding your data:

1. Personal data shall be processed fairly and lawfully.

2. Personal data shall be obtained only for one or more specified and lawful purposes, and shall not be further processed in any manner incompatible with that purpose or those purposes.

3. Personal data shall be adequate, relevant and not excessive in relation to the purpose or purposes for which they are processed.

4. Personal data shall be accurate and, where necessary, kept up to date.

5. Personal data processed for any purpose or purposes shall not be kept for longer than is necessary for that purpose or those purposes.

6. Personal data shall be processed in accordance with the rights of data subjects under this Act.

7. Appropriate technical and organisational measures shall be taken against unauthorised or unlawful processing of personal data and against accidental loss or destruction of, or damage to, personal data.

8. Personal data shall not be transferred to a country or territory outside the European Economic Area unless that country or territory ensures an adequate level of protection for the rights and freedoms of data subjects in relation to the processing of personal data.

Speaking on the issue, Karl Bantleman, Head of Digital at Direct365, commented:

“These figures show that most people are still worried about giving their sensitive information to companies. It’s down to businesses to demonstrate that they take data protection extremely seriously, and it’s vital that they reassure customers about their security policies and procedures.

“Perhaps the most worrying thing, however, is that so many people – particularly youngsters – don’t even safeguard themselves against potential data theft. Around half of the 18 to 24-year-olds that we spoke to freely admitted that they don’t shred documents like credit card statements and bills. This is asking for trouble.”

MD of consultancy-led security company Identity Methods, Ian Collard pointed out that the current Data Protection Act of 1998 was drawn up at a time pre-dating the widespread use of smartphones, social media and online banking. As such, it may no longer be fit for purpose.

“17 years ago less than 1% of Europeans used the internet. Today, vast amounts of personal data are transferred and exchanged across continents and around the globe in fractions of seconds. Suggesting that we adopt the old Act as our fallback position is akin to using veteran car laws to control modern motorway traffic.” he commented.

Back